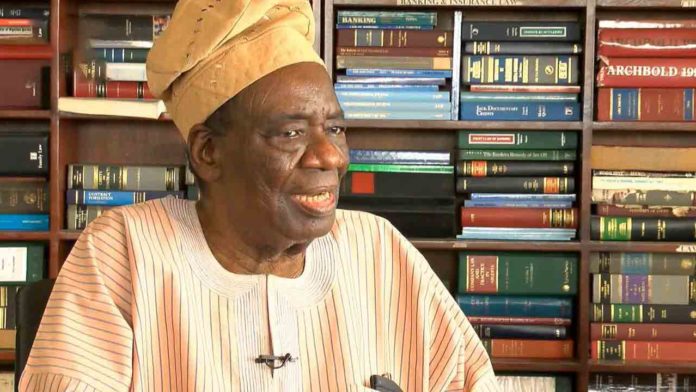

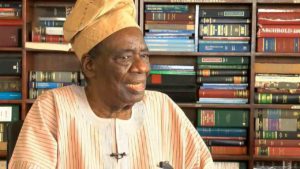

Chief Richard Osuolale Abimbola Akinjide (SAN, CON, CFR) who died on April 21, 2020 at the ripe age of 89 years, will forever be remembered as one of the most intriguing and accomplished Nigerians of Yoruba extraction. Although he was a frontline politician and legal luminary of repute, there are nevertheless, very few Statesmen whose careers courted so much embroilment in their lifetime and divided public opinion so sharply.

To some, he was reviled for being the political protégée of the late Chief Samuel Akintola, the Post Independence Premier of the Western Region of Nigeria. Both men were kindred spirits of sorts in that they bore striking facial similarities, notably their thick and pronounced tribal marks, and although Akinjide rarely mentioned his political mentor by name after his death, perhaps due to expediency, he left no one in doubt particularly those dismayed Awoists of the opposing camp that he was alive to fight and carry out the cause of his mentor from beyond the grave with invincible force. Then there were others (myself inclusive having served as his legal junior for over three years) who simply admired his legal genius, erudite mind, insatiable desire for knowledge and the fact that he was an oracle of wisdom, consistently linking the past with the present.

Early Beginnings and Introduction to Politics

Richard Akinjide was born on November 4, 1930 in Ibadan, in today’s Oyo state. He attended St Peter’s School Aremo Ibadan from 1937-42 for his primary school education. Thereafter, he proceeded to Oduduwa College, Ile-Ife from 1943-49 for his secondary school education where he passed his School Certificate with Grade 1. He travelled to the United Kingdom in 1952 for higher education and studied law. He was called to the English Bar in 1956 and later upon his return to Nigeria, he worked with the law firm SL Durosaro & Co for a short while before he established his own law practice of Akinjide & Co. Akinjide also showed keen interest in writing and wrote frequently for the West African Pilot and the Daily Times. Before long, he attracted the attention of Chief Adegoke Adelabu a.k.a. Penkelemesi, who at the time was the strong man of Ibadan politics. Adelabu recruited him into the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC). In 1959, Akinjide stood for election into the Federal House of Representatives from the South East Constituency of his native Ibadan and won, thus at the age of 29 he became one of the country’s youngest Parliamentarians.

After independence, Akinjide started to get disillusioned with the NCNC. Adelabu had died in a car crash on his way back to Ibadan from Lagos in 1958 and his inspirational leadership was no more. Although he was active in the Western Parliamentary Working Group of the Party, he soon noticed that many of the key positions at Federal level were being snapped up by the Igbo segment of the Party. After the Action Group (AG) crisis between Awolowo and Akintola in the early 1960s, Akintola desperately needed to recruit new, young and budding politicians to swell his ranks, particularly after most of his henchmen had abandoned him in favour of Awolowo. He moved in for those disgruntled Yoruba men in the NCNC and found amongst them a most talented individual in Richard Akinjide. Before long, he made Akinjide the General Secretary of his new Party, the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP) and nominated him to represent the Party in Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa’s government at the federal level who in turn appointed him Federal Minister of Education in 1965.

Akinjide’s tenure as Federal Minister of Education was somewhat controversial from the onset in that he acted upon the prejudices that were of great concern to him while he was in the NCNC. To begin with, he reduced the number of scholarships being awarded to students of Igbo descent at the time and broadened its spread to include other ethnic groups, but perhaps the most controversial decision of his short stint as Federal Minister of Education before it was cut short by the military coup of 1966 centred on the inter-ethnic tensions that flared up at the University of Lagos.

The Provincial Council of the University decided not to renew the term of Professor Eni Njoku who was serving as the pioneer Vice Chancellor of the University. The Provincial Council had decided to back a candidate of Yoruba ethnicity and Akinjide wasted no time in appointing and confirming Professor Saburi Biobaku as the University’s new Vice Chancellor. Shortly after his appointment the new Vice Chancellor was stabbed by a student radical called Kayode Adams, who believed the appointment was unfair and ethnically motivated, thereby leading many to question and scrutinise Akinjide’s rather hasty confirmatory appointment.

Soon after these tensions, the first military coup occurred on January 15, 1966 and Akinjide was one of several politicians that were detained by the military authorities at the time. He spent about 18 months in detention in various prisons in the country ranging from Kirikiri, Ilesha, Ibadan and Abeokuta. Upon his eventual release, Akinjide decided to devote more of his time and energy to legal practice. He even reportedly spurned an opportunity to join the government of Brigadier General Oluwole Rotimi (rtd) in the Western State of Nigeria and instead channelled all his efforts into legal practice.

One of the most important cases he handled at the time was as Counsel for the victims of the Asejire dam overflow in Ibadan. He succeeded in obtaining compensation for the victims thereby enhancing his status as a formidable lawyer. Before long, Akinjide rose to become President of the Nigerian Bar Association between 1970 -1973. Subsequently between 1975-1976, he was amongst the 49 wisemen that made up the Constitution Drafting Committee (CDC) entrusted with preparing a new Constitution for the Country in its transition to civil rule. He worked on the judicial aspect provisions sub-committee. In 1977, he also became a member of the Constituent Assembly, which consisted of elected and appointed officials tasked with examining and ratifying the draft 1979 Constitution.

Still Akinjide was not yet done. In 1978 he was amongst 12 distinguished members of the Nigerian Bar who were elevated to the rank of Senior Advocate of Nigeria. The 1978 batch of Senior Advocates was the second after that of 1975 which included Graham Nabo Douglas, the Attorney General of the Federation at the time and Chief Rotimi Alade Williams QC. The 1978 batch consisted of legal luminaries of distinction such as: Chief Obafemi Awolowo, Chief G.OK Ajayi, Kehinde Sofola, Olisa Chukwura, and Professor Ben Nwabueze (who is now the new leader of the Bar following Akinjide’s death) but to mention a few.

The Second Republic

In preparation for the Second Republic and the new political dispensation, Richard Akinjide joined the National Party of Nigeria (NPN) in 1978. A fellow Ibadan indigene by the name Chief Augustus Meredith Akinloye, who was a Minister with the Action Group in the Western Region and who had later joined Akintola along with Akinjide in the NNDP, became the new Chairman of the Party. Together with Akinjide they formed a formidable pairing within the Party.

Akinjide responded by stating that the free education programme provided by Awolowo in the 1950s was not as successful as made out and that in some instances it had even produced vagabonds, armed robbers, and the like. Bola Ige countered by stating that he was sure that members of Akinjide’s family must have benefited from the free education programme. He then asked whether Akinjide would be kind enough to tell viewers how many members of his family were vagabonds and armed robbers? Akinjide protested and said it was an insult and threatened to walk out of the programme and the studio unless Ige withdrew the statement. Ige insisted he only asked an innocent question to which he wanted an answer. Akinjide then carried out his threat and walked out of the studio.

Akinjide eventually lost the governorship election to Chief Bola Ige, but his party secured the highest number of votes in the 1979 presidential election. In the build-up to the 1979 election there were five registered political parties. The body presiding over the conduct of elections at the time was called the Federal Electoral Commission of Nigeria (FEDECO). Akinjide was already the legal adviser of the NPN. The 1979 presidential election got caught up in a mathematical controversy. FEDECO announced that NPN had polled 5,688,857 votes while its closest rival, the UPN, polled 4,916,657 votes.

However, the 1979 Constitution provided that in order to become President a candidate had to secure at least 25 per cent of the votes cast in 2/3 of the 19 states of the Federation. Alhaji Shehu Shagari had 25 per cent in 12 states but failed to secure 25 per cent of the votes cast in all the other states. Akinjide, perhaps mindful of the Privy Council case of Adegbenro vs Akintola 1963 AC 614, was aware of the fact that in deciding constitutional issues you could not impute any other but its clear meaning in interpreting the provisions of a written Constitution. Therefore, Akinjide argued, that 2/3 of 19 states was not 13 but 12 2/3 and that all that his client needed was to satisfy FEDECO that he had secured 25 per cent of the votes in 2/3 of another state, which in this case happened to be Kano. In Kano, Shagari polled 243,42 votes- the equivalent of 19.4 per cent of the 1,220,763 votes cast in total in the state. This amounted to 25 per cent of the votes cast in 2/3 of all the entire local governments of the state.

In my opinion, what the Supreme Court meant was that it was incumbent on the legislature in the form of the National Assembly to amend the Constitution to allow for certainty in the law rather than quote their judgment as precedent in the future. This was also the lesson our Courts had learnt from Adegbenro vs Akintola (supra) where a controversial decision of the Privy Council, ultimately led to the government retroactively amending the Constitution of the Western Region in 1963. The Federal Government also later dispensed with appeals to the Privy Council by amending the 1963 Constitution so that it would conform with Republican status. The Supreme Court had clearly learnt that if there was a perceived lacuna in the Constitution it was for the legislature to ideally address this anomaly. In Awolowo v Shagari many commentators felt a fraction should be rounded up to the nearest whole figure but as we learnt from Adegbenro v Akintola (Supra) it’s for the Constitution to specifically state this fact.

Richard Akinjide’s reward for this outstanding legal reasoning was that he was appointed Attorney General and Commissioner of Justice for the Federation. His tenure as Attorney General of the Federation was steady, but still laced with controversy, as we had come to expect from Akinjide. Under his watch, Nigeria temporarily abolished the execution of armed robbers. He also abolished a decree barring exiles from returning to Nigeria. However, the case of Minister of Internal Affairs v Shugaba Darma 1982 3 NCLR 915 was the one case that was perhaps the most controversial during his tenure as Nigeria’s Chief law officer. Shugaba was a charismatic politician from the North East of Nigeria, in Maiduguri to be precise. He was always able to draw large crowds wherever he spoke and he was often very critical of the ruling NPN. Overnight, Shugaba was deported to a village in the neighbouring Republic of Chad on the grounds that his father was from there and as such he was not a Nigerian. Shugaba’s mother though was a Nigerian but the authorities sought to cover up this fact and brought a Chadian woman at trial claiming she was Shugaba’s mother.

Aftermath of the Second Republic

Akinjide spent his 11-year period of self exile in the UK engaged in legal practice. He was first engaged at the United Nations in a consultancy role working on International Conventions on the Law of the Sea. He also took advantage of the fact that he had qualified from the Inner Temple as a Barrister in the 1950s to join a reputable tenancy at 10 Kings Bench Walk in the Chancery, Central London. While in Chamber he handled a series of cases ranging from criminal, civil, employment and tenancy matters. He also became a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators and engaged himself in several commercial arbitrations. By the time President Abacha came to power a major boundary dispute had arisen between Nigeria and Cameroon over the Bakassi Peninsula. President Shagari was consulted by the Federal Government for advice on what to do and he in turn referred them to the expertise of Richard Akinjide, his erstwhile Attorney General. Abacha made immediate contact with Akinjide in London thereby setting the stage for his eventual return home in 1994. Akinjide handled the Bakassi dispute on behalf of Nigeria at the World Court for several years. He also utilised his immense legal standing as a lawyer at home and abroad to rebuild his legal practice. Three of his children Jumoke, Abayomi and Bimbo were practicing Solicitors in the City of London. His daughter, now Oloye Jumoke Akinjide, a former Minister of State of the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja was one of them and she eventually returned to Nigeria and played her part in rebuilding Akinjide & Co. Before long the practice was fully rebuilt and Akinjide had retainers with major oil firms, banks and other commercial entities both at home and abroad. He also continued to be engaged in commercial arbitration.

As Akinjide matured in years he continued to contribute his fair quota to the National debate. He was a member of The Patriots, a body of grandee Statesmen made up of the likes of the late Chief Rotimi Williams and Professor Ben Nwabueze, but to mention a few. Their aim was to actualise a restructured Nigeria. Akinjide actively participated in the National Conference deliberations of 2014 set up by President Goodluck Jonathan and he had the singular honour as one of the oldest delegates at the Conference to bring the deliberations and conclusions of the Conference to a close.

Richard Akinjide lived an accomplished life, full of beguile and intrigue. He was revered by friends and foe alike as both a political titan and a legal colossus. He was in fact a simple man who was introspective and loved the basic things of life such as reading and writing. He enjoyed the company of trusted friends who stimulated conversation and aroused his intellectual curiosity. Above all, he ran a quiet and peaceful home with his wife and children. Up until the time of his death, he was always involved in the national debate, trying to shape a right and proper course for Nigeria. Some have argued that in his later years, he began to back-track from his early views and was attempting to put right his historical wrongs. I firmly disagree. Richard Akinjide merely saw politics as a means to an end, as an opportunity to be seen and heard like a performer on stage. He realised early enough that you had to choose which play you wanted to feature in.

Initially, he chose the NCNC because of his affiliation to Adelabu, but tribal and ethnic concerns made him form the view either rightly or wrongly, that the North could provide an easier platform to get onto the centre-stage he craved. Having secured his place on that stage he became a star performer featuring in many leading roles for well over six decades eventually maturing along the way like that great old grandee of British Theatre, Laurence Olivier. He was indeed the last of the Mohicans in that I doubt whether there is any other active participant on the political stage that can accurately thread the past through to the present.

The Guardian