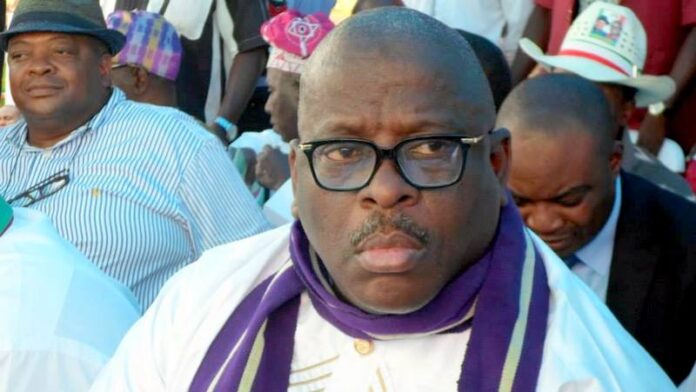

Buruji Kashamu, until his death had used the last 22 years fighting the plans to extradite him to the United States to face a drug charge filed as Case No. 1:94-cr-00172.

The United States since 1998 had tried to get him to face trial, first by filing two extradition requests against him in the UK. But the moves failed.

The battle continued in Nigeria.

Kashamu, a dual citizen of Nigeria and Benin, was charged in an indictment returned by a federal grand jury in Chicago, Illinois, along with 13 other persons, with conspiracy to import heroin into the United States and distribute it in 1998.

The Jury had agreed that Kashamu was the leader of the drug cartel and he was indicted both in his own name and under what the government believed to be two aliases that he used: “Alaji” (the principal alias, the government thought) and “Kasmal”.

But Buruji used the instrumentality of the law and consistent pleading of innocence and mistaken identity to avoid being shipped to the U.S.

P.M News has reprinted the case, which has even been the subject of a movie.

United States of America v. Hayes et al

Illinois Northern District Court, Case No. 1:94-cr-00172

District Judge Charles R. Norgle, Sr, Presiding.

After lawyers to Buruji Kashamu moved a Motion to quash the arrest warrant issued by Judge Charles R. Norgle in this case, US government’s issued a detailed response saying the motion should be denied because principles of res judicata do not apply to extradition proceedings and the government may initiate multiple extradition proceedings against Kashamu in an effort to secure Kashamu’s appearance in this case.

I. Background

In March 1994, defendant Kary Hayes, a passenger arriving at O’Hare International Airport (“O’Hare”) on a flight from Zurich, Switzerland, was arrested after he tried to smuggle into the United States a suitcase containing approximately 14.16 pounds of heroin. Hayes was one of a long line of couriers in a heroin smuggling operation led by Kashamu. Kashamu arranged: (a) the pick up of the heroin by the couriers in Europe and Indonesia; (b) the transfer of the heroin to others once the heroin entered the United States; (c) the payment of the couriers and the people who supervised them; and (d) the carrying by couriers of large sums of cash during the couriers’ outbound trips from the United States for delivery to him in Europe and elsewhere. The government charged Hayes and other couriers after this initial arrest. Many of these couriers cooperated and provided information about their contacts with Kashamu.

A. The charges against Kashamu

On May 21, 1998, a grand jury charged Kashamu and others in a Second Superseding Indictment with conspiracy to import heroin into the United States in violation of Title 21, United States Code, Section 963. Between July 7, 1998 and January 27, 1999, nine of the fourteen defendants named in the Second Superseding Indictment pled guilty. These nine defendants admitted their participation in the heroin smuggling organization and all acknowledged that Kashamu, the man they called “Alaji” or “God,” was the person ultimately in charge of the heroin smuggling organization. Some of these couriers, including defendants Catherine Cleary Wolters and Nicholas Fillmore, Jr., had visited with Kashamu at his residence in Benin in connection with the heroin smuggling organization. One of the couriers, defendant Ellen Wolters, had a romantic relationship with Kashamu. The smuggling trips and trips to visit Kashamu in Benin were documented by, among other things, money transfer orders from Western Union and American Express, flight records, credit card charges, hotel records, and telephone call detail records. The telephone records, for example, reflected calls from the couriers to Kashamu’s residence in Benin.

B. Kashamu’s arrest and the initiation of extradition proceedings

The government requested the issuance of a provisional arrest warrant against Kashamu based on information that he travelled to London, England on occasion. On December 18, 1998, the Metropolitan Police arrested Kashamu in London, England when he arrived on an inbound flight. Kashamu was found in possession of approximately $230,000 in cash at the time. Kashamu travelled under the name “Kashamu” and possessed identification documents including a passport from Benin, “Carte Nationale D’Identite” from the Republique du Benin, and a business card bearing the notation “Group Kasmal International, Import-Export-Industrie, Representant Exclusif, Daewoo & Sang Yong Motor.” One of the addresses listed for “Group Kasmal International” on the business card was a location in Cotonou, Benin. Three of the defendants had described to the government prior to Kashamu’s December 18, 1998 arrest what they understood to be some of the businesses with which they understood “Alaji,” the leader of the heroin smuggling conspiracy, to be associated. Catherine Wolters, for example, stated that “Alaji” owned “Kasmal Exports” in Benin. Fillmore stated that “Alaji” owned in Benin an import/export company called “Kasmal” and an automobile dealership called “Daewood.” Barry J. Blow stated that “Alaji” lived in Benin and imported rice and was involved in a car dealership in Belgium.

Kashamu was ordered detained following his December 1998 arrest and he was incarcerated in London’s Brixton Prison during the pendency of extradition proceedings based on the government’s warrant in the instant case. Kashamu’s arrest triggered the commencement of the time limit for the government’s submission in support of extradition. Extradition proceedings arising from warrants issued in pending federal cases are coordinated through the Department of Justice’s Office of International Affairs (“DOJ OIA”). The paperwork in support of the extradition, including the affidavits in support of the extradition, however, is compiled initially at the local level, in this case by the undersigned attorney. The government is required, as a part of the extradition proceedings, to establish identity, i.e., a link between the person arrested and the person charged. The undersigned attorney compiled affidavits from, among others, Catherine Wolters and Fillmore concerning their interaction with Kashamu and their identification of him in a photospread.

Both Catherine Wolters and Fillmore had, prior to Kashamu’s December 18, 1998 arrest, identified a photograph of Kashamu from a photospread as the person whom they knew to be in charge of the heroin smuggling organization. The case agents referred to the photograph of Kashamu as the “surveillance” photograph because the agents believed at the time that overseas law enforcement officers had taken the photograph while on surveillance. The government obtained a copy of Kashamu’s December 18, 1998 arrest photograph and placed it into a photospread The government showed Fillmore this second photospread at some point after Kashamu’s arrest and before transmitting the extradition paperwork to DOJ OIA. Kashamu’s arrest photograph appeared in Position 7 of the photospread.

As Fillmore viewed the arrest photospread, Fillmore stated “it’s not jumping out at me” and that he knew what “Alaji” looked like. Fillmore told the agents that the photograph in Position 3 looked like a bad photograph of “Alaji” and that the photographs in Positions 2,4,6, and 7 did not look like “Alaji” at all. Fillmore stated that the photograph in Position 5 looked a lot like “Alaji” but also did not look like him. Fillmore ruled out the photograph in Position 1 and stated that the photograph in Position 5 looked the closest to “Alaji.

In February 1999, agents from the United States Customs Service showed another cooperating defendant, Brian Christman, Kashamu’s arrest photograph. Christman could not make a positive identification of Kashamu, the person whom he also knew as “Alaji,” from the photograph. The arrest photograph of Kashamu was not a part of a photospread when agents showed the photograph to Christman.

In February 1999, while preparing the extradition paperwork, the undersigned attorney advised the DOJ OIA lawyer assigned to the extradition case that Fillmore had not identified Kashamu’s arrest photograph in a photospread and had instead indicated that another photograph in the photospread looked more similar to the person whom he knew as “Alaji.”

The undersigned attorney also explained Christman’s inability to positively identify “Alaji” from the arrest photograph. The undersigned attorney asked the DOJ OIA lawyer whether the government needed to disclose the information about the viewing by Fillmore and Christman of the arrest photograph in the affidavits of Fillmore and Christman attached to the extradition submission. The DOJ OIA lawyer advised against the inclusion of the information because the extradition treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States did not require that such disclosures be made.

C. The first extradition proceeding

In approximately February 1999, the United States, through DOJ OIA, and the Crown Prosecution Service, the representative of the United States in the extradition proceedings, timely submitted the extradition package to the London court. In May 2000, as part of the extradition proceedings, Kashamu submitted documents in which he claimed for the first time that, prior to his December 1998 arrest, he cooperated with law enforcement authorities in Benin, Togo and Nigeria and that he told these authorities that his brother, Adewale Kashamu, was involved in drug trafficking activity. The government had no knowledge of any alleged cooperation by Kashamu or of the existence of any alleged brother before Kashamu made these claims. The undersigned attorney again raised with the DOJ OIA attorney the issue of disclosing the results of the viewing by Fillmore and Christman of the arrest photograph. The DOJ OIA attorney again advised against disclosing the information.

On or about May 28, 1999, Metropolitan Magistrate Timothy Workman committed Kashamu to prison to await extradition to the United States. GEx4. On or about June 11, 1999, Kashamu through counsel sought permission to apply for judicial review to quash the committal order. At some point, during the pendency of this review, the government, through the Crown Prosecution Service disclosed the information about the viewing by Fillmore and Christman of the arrest photograph. On October 6, 2000, the High Court of Justice, Queen’s Bench Division, ruled that the “committal order must, in the circumstances, be quashed by reason of the unfairness of the proceedings resulting from the non-disclosure of crucial evidence [the Fillmore response to the arrest photograph], as accepted by the Government.” The Court noted that “[i]f they seek to proceed, the Government need to seek a fresh warrant.” Id. at 7, ¶ 29.

D. The second extradition proceeding

The government obtained a new warrant against Kashamu and executed it before Kashamu was released from custody. A second extradition proceeding was thereafter initiated before Magistrate Workman, the same judge who had considered the first proceeding. The government submitted additional materials to show that Kashamu, the person in custody, was the same person as “Alaji,” the leader of the heroin smuggling conspiracy. The government, for example, showed the arrest photospread separately to defendants Catherine Wolters and Ellen Wolters. Both Catherine Wolters and Ellen Wolters identified the photograph in Position 7 (Kashamu) as the person whom they knew as “Alaji.” The government also separately played for Catherine Wolters and Ellen Wolters a recording of a telephone conversation Fillmore had with “Alaji” in 1996 after Fillmore began to cooperate with the government. Both Catherine Wolters and Ellen Wolters, as Fillmore had previously, identified the voice on the recording as that of “Alaji.” The Wolters sisters were in different states when they each viewed the arrest photospread and listened to the recorded conversation. The government’s submission included affidavits from Catherine Wolters, Ellen Wolters and Fillmore setting forth these identifications, and an affidavit from Special Agent Daniel.

Morro describing the process he employed in showing the arrest photospread and in playing the recorded conversation. The Fillmore affidavit also described Fillmore’s earlier viewing of the arrest photospread and Fillmore’s responses. The government also included a copy of the recorded conversation in the submission as well as a transcript of the conversation. On or about November 29, 2000, the DOJ OIA, through the United States Embassy in London, presented these new submissions, as well as the submissions from the first extradition proceeding, to the Crown Prosecution Service for use in Kashamu’s second extradition proceeding.

On or about December 2, 2000, the undersigned attorney informed one of the Crown Prosecution Service attorneys representing the United States in the second extradition proceeding that the case agents had learned that the photograph referred to as the “surveillance” photograph of Kashamu had been supplied by a confidential informant. The Crown Prosecution Service relayed this information to Kashamu’s attorney in the second extradition proceeding.

On March 13, 2001, Magistrate Workman refused to hear and determine Kashamu’s claim that the institution of the second extradition proceeding amounted to an abuse of process and that the proceeding was oppressive. Magistrate Workman suggested that the abuse of process claim be submitted to the High Court for review to determine the appropriate forum in which such claims should be considered. Kashamu filed an application for habeas corpus and judicial review with the High Court in connection with Magistrate Workman’s refusal to hear his abuse of process claims. At some point in 2000, Chicago attorney Thomas Anthony Durkin notified that government that he had been retained as Kashamu’s United States-based attorney. The High Court combined Kashamu’s habeas application with that of two other individuals whose extradition was also being sought by the United States.

On November 23, 2001, the High Court ruled that the Magistrate’s Court, and not the High Court, was the appropriate forum to hear evidence and submissions and making findings of fact as to abuse of process. The High Court returned the case to the Magistrate Court for the resumption of the second extradition proceeding.

The second extradition proceeding before Magistrate Workman focused primarily on two claims raised by Kashamu to challenge his identity: (1) Kashamu was a cooperator with the Nigerian Drug Law Enforcement Agency (“NDLEA”); and (2) Kashamu told the NDLEA, among other things, that his alleged brother, Adewale Adeshina Kashamu, whom Kashamu claimed looked remarkably similar to him, was a drug trafficker. The parties submitted evidence about Kashamu from Nigeria, through various officials including those associated with the Nigerian Drug Enforcement Administration “NDLEA”), as well as from other West African countries including Benin and Togo. This foreign evidence was at times contradictory.

Throughout the second extradition proceeding, Kashamu’s counsel levied accusations of misconduct against the government’s identification evidence and the responses the government had obtained from foreign officials.

E. The identification of Kashamu’s arrest photograph by the Wolters sisters

On or about October 23, 2001, Akhtar Raja, Kashamu’s counsel, submitted an affidavit to Magistrate Workman in which he claimed that the additional identification evidence was “profoundly tainted” because the undersigned attorney had “given [to the Wolters sisters] details of the [October 6, 2000] judgment” of the first extradition proceeding which referenced the position of Kashamu in the arrest photospread. The undersigned attorney had not disclosed to either Catherine Wolters or Ellen Wolters, or to their respective attorneys, the position of Kashamu’s photograph in the arrest photospread.

On or about November 16, 2001, the undersigned attorney submitted to the Crown Prosecution Service letters dated November 6, 2001 from Alan A. Dressler, attorney for Catherine Wolters, and from Steven R. Shanin, attorney for Ellen Wolters. Mr. Dressler stated that the claim that he had been given details of the October 6, 2000 judgment was “categorically untrue.” Id. Mr. Dressler stated that neither he nor his client knew in advance of viewing the photospread the position of Kashamu’s photograph. Id. Mr. Shanin stated in his letter that to the best of his recollection he never received copies of any of the documents concerning the extradition proceedings and that neither he nor his client had any advance knowledge of the position of Kashamu in the photospread or even if the photospread contained Kashamu’s photograph. Id. Mr. Shanin further stated that Ellen Wolters’s identification of Kashamu “was spontaneous, without any hesitation, and without any impropriety whatsoever on the part of any government agent including AUSA MacArthur.” Id.

F. The contradictory evidence concerning Kashamu’s status as a cooperator

The United States government sent an inquiry to Interpol in Benin, Togo and Nigeria about whether Kashamu ever acted as a cooperator with their law enforcement agencies. In April 2000 (received by the undersigned attorney in October 2000), Interpol Benin responded that Kashamu, “a well-known businessman in Cotonou,” “collaborated with the police of Benin (BCN-IP Cotonou) within the scope of the fight against drug trafficking from 1993 to 1995.”

In July and August 2000, Interpol Togo relayed that Buruji Kashamu “had provided service to Togo” from 1990 to 1997 “in the area of information concerning narcotics traffickers” and that the “Chiefs of the Immigration Service … and Interpol” confirmed that Kashamu provided “confidential information concerning his brother the man named Adewale Adeshina Kashamu who also belonged to a drug trafficking network.”4 The undersigned attorney forwarded these responses to DOJ OIA and to the Crown Prosecution Service for production to Kashamu’s counsel.

On or about October 11, 2001, the undersigned attorney received from the United States Drug Enforcement Agency (“DEA”) office in Lagos, Nigeria a telex referring to “information” received by the DEA from the NDLEA on March 12, 2001. GEx8. On or about November 8, 2001, the undersigned attorney received by facsimile transmission from DEA Special Agent Vincent Fulton, who was stationed in the DEA’s Lagos office, a “fax transmittal sheet” with an attached letter dated March 12, 2001 from the NDLEA. Id.. The NDLEA letter was addressed to “The Ambassador of the Embassy of the United States of America” and was signed by B. Lafiaji, Chairman of the NDLEA.

The March 12, 2001 letter from Chairman Lafiaji represented that Kashamu “had, at no time, been an informant of this Agency (NDLEA) nor has the Agency had cause to reward him for anything.” Id. The letter also stated that “Alhaji Adewale Adeshina Kashamu, a wanted drug suspect, was already dead by the time Buruji Kashamu was wanted by this Agency in 1994, having died while attempting to run away from Customs investigation for involvement in drugs.” Id.

Kashamu presented in the second extradition proceeding a letter dated January 24, 2000 on NDLEA letterhead purportedly signed by O. O. Onovo, “Chairman, Chief Executive, NDLEA.” The letter stated that “[y]our client [Kashamu] has been very helpful to us in the area of fighting crime and we are surprised that he is being incarcerated on wrong accusation of drug trafficking in the UK.”

On November 9, 2001, the day after receiving the NDLEA letter Initially, in June 2000, Interpol Togo responded that “the man named Buruji Kashamu [with the same date of birth as “Buruji Kashamu”] … is unknown in the Anti-Narcotics Brigade of the National Central Bureau–Interpol Lome.”

Representing that Kashamu was not a cooperator, the undersigned attorney requested by facsimile transmission that DEA Lagos seek a response from the NDLEA about these conflicting letters. Id. On or about November 15, 2001, the undersigned attorney received from Special Agent Fulton a letter on NDLEA letterhead dated November 15, 2001 signed by U. Amali, the Special Assistant to the Chairman and Chief Executive of the NDLEA. Id.. The letter stated that the letter submitted by Kashamu dated January 24, 2000 (as well as a letter dated January 13, 2000) were “bogus” and their contents “absolutely false.” Id. The undersigned attorney informed the Crown Prosecution Service of these responses. Kashamu thereafter submitted affidavits which purported to be from Iliya Mshelia, Chief Prosecutor and Deputy Director in the Legal Services Department of the office of the NDLEA Chairman/Chief Executive and Samson Aboki, Director of Public Prosecution of the NDLEA.

The undersigned attorney received these submissions on or about February 4, 2002. Magistrate Workman had scheduled a hearing in the second extradition proceeding on February 7, 2002. The undersigned attorney immediately requested Special Agent Fulton’s “rapid assistance” in finding out from the NDLEA, if possible, whether the two new affidavits were valid and whether the purported affiants even existed. GEx8. The next day, on or about February 5, 2002, the undersigned attorney received from Agent Fulton a letter on NDLEA letterhead dated February 5, 2002 from Usman Amali, Chairman/Chief Executive of NDLEA. Id. Chairman Amali stated in the letter that Kashamu “has never been an informant or source of this Agency, rather he is a fugitive drug offender on the run from arrest, please.” Id. The undersigned attorney forwarded this response to the Crown Prosecution Service.

Magistrate Workman’s February 28, 2002 Decision to Allow the Second Extradition Proceeding to Move Forward to the Defense Case. On or about February 28, 2002, at the conclusion of the government’s presentation of its case, Magistrate Workman held that, “subject to any further evidence I am asked to consider, I am of the view that these issues [of the identification process] touch upon the fairness of the trial itself and, if there is any abuse of process, it will be for the trial judge to consider whether a fair trial is possible rather than whether it is unfair to try the defendant. For my own part I think these issues are essentially matters of admissibility and credibility rather than an abuse of process.” Magistrate Workman concluded that “[i]n the light of this decision the court will now have to move to consider the evidence and the sufficiency of the arguments.” Id. The proceedings then shifted to Kashamu’s affirmative presentation of evidence, including witness testimony, and the government’s rebuttal of that evidence.

G. Kashamu’s affirmative presentation of evidence

On or about May 9, 2002, Magistrate Workman conducted a hearing in Kashamu’s second extradition proceeding. Before the hearing, Kashamu presented a letter in which NDLEA “Chairman” Amali purported to represent that Kashamu was not arrested in 1994 and was not “on the list of persons wanted for prima facie drug offenses by the Agency, per se.” The letter also represented that Kashamu’s brother had not died in the custody of the Nigerian Customs Service. Kashamu’s submission revealed that Kashamu had sued the NDLEA because the NDLEA had not, in Kashamu’s view, retracted the negative information in its letters about him. The undersigned attorney received Kashamu’s submission on or about May 5, 2002 and immediately thereafter requested that Special Agent Fulton in Lagos find out why there had been such an apparent change in the NDLEA’s position on Kashamu’s status. Id. The request to Agent Fulton contained certain questions to pose to the NDLEA representative. Id.

On May 8, 2002, the day before the hearing, the undersigned attorney received from Agent Fulton a letter on NDLEA letterhead dated May 8, 2002 signed by Usman Amali, Special Assistant to the Chairman/Chief Executive of the NDLEA, which contained answers to the posed questions. Id. The letter stated that “[t]he Agency stands firmly by its earlier assertion that Buruji Kashamu has never been a cooperator with NDLEA” but that, after being presented with a passport issued in 1990 to Adewale Kashamu, the Agency found it “difficult to continue to assert [its] earlier conclusion that Adewale Kashamu died in the custody of the Nigerian Customs Service before the establishment of NDLEA in 1989.” Id. The letter confirmed that Kashamu’s attorneys had “threaten [ed] to take legal action against the Agency and the Federal Government of Nigeria if the letters were not retracted.” Id. The undersigned attorney forwarded the response to the Crown Prosecution Service.

On or about September 17, 2002, through DOJ OIA, the United States Embassy presented to the Crown Prosecution Service an additional submission for use in the second extradition proceeding. This submission compiled the communications between the undersigned attorney, the DEA agents in Lagos, and the NDLEA responses. The submission also included, among other affidavits, sworn affidavits dated July 29, 2002 from NDLEA Chairman Lafiaji and Special Assistant Amali. Chairman Lafiaji confirmed that his statement in his March 12, 2001 letter that Kashamu remained a wanted suspect in Nigeria was accurate based on information that had been compiled and was known at that time.

SAHARA REPORTERS